Some days it seems as though we all have to become armchair biologists just to make everyday decisions. During the COVID-19 pandemic, we have been challenged to brush up on the basics of how viruses spread and to constantly evaluate the risk of exposure for ourselves and our loved ones. That is just one example of the ways that ordinary people apply the life sciences to make decisions in the real world.

"Disease, pollution, food, how our bodies work, how your hair is curly or straight—everyone is inherently interested in knowing how these things work." enumerates M. Ruth Elliott, a lecturer in biochemistry for Penn's College of Liberal and Professional Studies. We may also find ourselves reviewing scientific sources and using scientific reason to make personal choices, such as dieting and meal planning, or complex decisions such as establishing environmentally sustainable practices in the home or workplace, she adds.

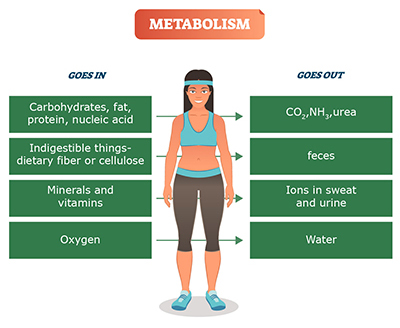

With that in mind, Elliott and her LPS colleague Kieran Dilks developed PHYL 120: Foundations of Life Sciences to provide an introduction to biology as well as practice in scientific reasoning. "Life science is the study of living organisms of all kinds," explains Elliott. "We will cover the basics of cell biology, molecular biology, ecosystems, genetics, and metabolism." Open to all Penn LPS Online students, Foundations of Life Sciences is designed to make basic biology and the scientific method accessible to adult students whether or not they have prior experience in the subject or plan to continue taking online science courses.

"The goal is to create an easy way to access life science, biology, and scientific reasoning," says Elliott. "Giving students the basis of biological thinking and a way to dissect scientific arguments gives them the power to make decisions about their daily lives."

What is scientific reasoning—and what does it have to do with you?

"There's some kind of scientific process that happens in every human brain. Eventually, two-year-olds figure out if they drop things, they fall to the floor, right?" laughs Elliott. "A lot of the weekly activities are trying to tap into that process." While Elliott and course co-developer Dilks do not strictly recommend replicating the process of toddler experimentation, that spirit of curiosity followed by inquiry, experimentation, and observation animates much of the Foundations of Life Sciences course material. In addition to video lectures, discussion boards, and problem sets, this introductory online course includes weekly activities focused on putting scientific method into practice.

"Each week, students complete an activity where they are thinking about variables, how the variables relate to each other, how to measure outcomes, and how to interpret the results of experiments," explains Elliott. Some activities involve studying traditional experiments, such as the process that determined that DNA is the genetic material that passes family traits to children. "Looking at traditional experiments helps students learn a way of thinking and making scientific arguments. The activity is aimed to help students realize they can interpret the results of the experiments too. They can understand the experimental process and come to a conclusion as well," explains Elliott. "The habit of thinking experimentally is relevant and useful in any field."

Other activities, such as one focused on studying identifying threats to a specific ecosystem, are assigned to expose students to different biological fields and develop their appetites to explore topics in the life sciences. In activities as well as on discussion boards, students are invited to bring up topics that interest them and make relevant connections to course material. "So just as the Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences (BAAS) degree is intended to allow students to customize their curriculum, we set up assignments the same way," says Elliott. "Take this concept and apply it to the topics you are most interested in."

Elliott and Dilks envision the course as an opportunity to position adult students for further study in the life sciences. "If students are interested but don't feel they're quite ready to jump into the course blocks that exist, this is one of the courses they can take to dabble in the sciences and ask, Am I interested? Can I do this? What is the way of thinking like for this discipline?" explains Elliott. But even students who don't intend to undertake a degree or certificate in the sciences can benefit from the material.

"People have to make science-based decisions all the time. You make decisions about your health or your diet, making decisions about your home or your businesses being green," says Elliott. "Navigating decisions about your lifestyle can involve reading a lot of arguments about why you should do this or that, why you should eat this or that, when you should exercise, and so on." This is already a form of scientific method, from gathering and evaluating data to observing results and drawing conclusions—and more exposure to solid scientific resources and successful methods can enhance and refine the decision-making process.

Developing an online science course for busy adults

"Foundations of Life Science is not based on any existing course at Penn. It's brand new," says Elliott. The introductory course fulfills different needs for adult students who enroll at different stages of their education. Non-degree students may benefit from an introduction to biology before pursuing a Certificate in Neuroscience or a Certificate in Climate Change, particularly if they have any apprehension about taking an online college-level science course. For the same reason, Foundations of Life Sciences makes an excellent introduction for BAAS students who wish to pursue the Physical and Life Sciences degree concentration. For BAAS students who aren't planning to pursue a science education, the course may be applied to the Scientific Reasoning foundational requirement for the degree. Foundations of Life Sciences can also be taken as part of the Gateway Program in which prospective BAAS students take courses across subjects to demonstrate academic abilities prior to enrolling in the degree.

"It's hard to envision Penn LPS Online students as a group," reflects Elliott. "Every one of them is going to be an individual with a story about why they want to go back to school and what they have done already." A classroom with varied experiences is not a new experience for Elliott or Dilks, both of whom teach courses in Penn's Pre-Health Programs, which helps prepare post-baccalaureate students for health professional school whether or not they studied science as undergrads. Dilks also leads a summer science academy for high school students. "It's great to have someone who knows what early science learners are going to hear, what their pitfalls might be, and which topics might require more reinforcement," says Elliott. Dilks particularly lent his expertise to develop the introductory material in the first few weeks of class.

The 8-week course is accelerated, says Elliott, but designed to provide students with the building blocks they need to advance their scientific reasoning. For example, one of their weekly activities assigns each student a short DNA sequence and asks them to identify it using an online, open-source tool called BLAST provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Once they have determined which common pathogen their DNA sequence belongs to, they can apply what they have learned in the class to understand how these infections are treated. "I think it's pretty cool that you can take a short DNA sequence, type it into an engine that is freely available on the internet, and find out what it is," says Elliott. "But what I'm excited about is that students will have the ability to understand why germs become resistant to the medicines that are used to treat them and learn real-life examples of how that works. That might sound like knowledge for people with PhDs, but it's something that they'll be able to understand after three weeks of biology."

Cooking up an online science course from home

Elliott and Dilks expected to record their course materials in Penn LPS Online's on-campus studio this summer. Instead, they found themselves taking on the role of ad hoc video producers while coordinating remotely with Penn's online learning team. "There have been some real challenges," laughs Elliott. "The online learning team has been very supportive and very innovative themselves with figuring out how to support a bunch of people in their own houses on their personal Wi-Fi."

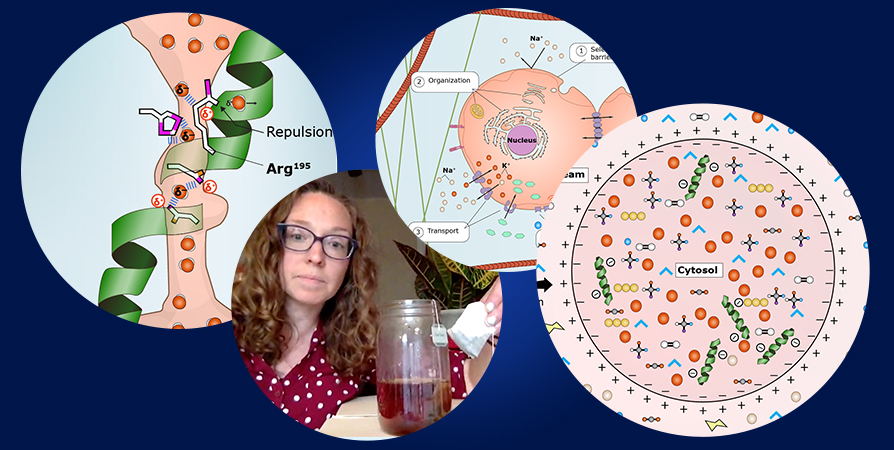

Fortunately, the online format lends itself to remixing and pushing the boundaries of a traditional classroom environment. For example, scientific experts such as a cancer biologist from Penn's Wistar Institute can drop in for an online guest lecture and talk about their work on video. Elliott was also grateful for Penn LPS Online's in-house illustrator to enhance their course materials; "Penn is so committed to high-caliber online courses that we have artists and musicians helping to make this biology class go out," she says. While Elliott and Dilks assigned a book called Biology: How Life Works, which naturally includes diagrams and illustrations, they didn't want to simply teach to the textbook and requested supplemental images. "Science is so image-heavy. You can't really picture mitochondria without having an image of it," Elliott adds.

For other videos, the course developers worked with what they had close to hand. Teaching and working from home with his family, Dilks recorded some of his instructional videos from his backyard with planned and unplanned appearances by his children. For a video focused on the biological process of fermentation, Elliott grabbed examples from the refrigerator she shares with her housemates. "These lecture videos are happening in our homes, not separated from our personal lives," she says. Of course, conducting their science classroom from their kitchens and backyards just drives home the point that science is everywhere. And just as Elliott and Dilks can teach from home, so can students learn wherever they happen to be.

Finding opportunities for everyday science is central to Elliott's advice for students who are new to the subject. "Reach out for help as soon as possible. Use the practice questions to help you work through lectures. Do a little every day so that you're not overwhelming yourself," Elliott suggests. Above all, "try to see how the things you're learning apply to the world around you, because that serves as motivation to keep going when there is a tricky concept."

Interested in more in-depth scientific study? Read about our neuroscience courses in "Your mind at work: Applying neuroscience in the classroom and outside of the lab," and our climate change courses in "What is climate change, and what should we do about it?"