Features

Equipped with lessons in leadership, vocalist Katie Elliot helps direct a new opera company's vision

Meet the team behind the help desk: the School of Arts and Sciences Online Learning operations team

Professional dancer and BAAS student Avery Ambrefe starts her second season with the Radio City Rockettes this fall

Student-parents understand: BAAS alumni share how online learning at Penn helped them find school-life balance and more

Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences graduates honored as 2025 LPS Student Award winners

Discovering passions, becoming a leader, and forging connections: Recent BAAS graduates share their stories

Data analytics: solving real-world problems one formula at a time with computational social science

Unveiling the intricacies of neurochemicals: exploring their role in brain function and mental health

For these career changers, Penn LPS Online certificates are “just right” for their goals

Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences graduates honored as 2024 LPS Student Award winners

Building a professional network online: How to connect with your peers and working professionals in a virtual environment

Why a Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences in Organizational Studies is critical in today’s world

Interested in applied positive psychology? Explore 5 exciting career paths enhanced by positive psychology

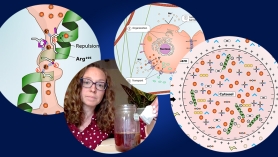

Penn LPS Online Neuroscience Certificate student Kelley Roark writes about the neuroscience of epilepsy in web journal Neuro Central

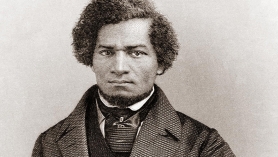

Can learning about ghosts help us cope with pandemic losses? This Penn professor says yes.

Interested in a sports marketing career? Elevate your marketing skills with the Certificate in Digital Strategies and Culture

Interested in all things related to technology? Explore 5 exciting digital marketing career paths

Tell a compelling career story with the Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences Senior Portfolio

LISTEN: Professor of Music guides listeners on a tour of South African music history for OMNIA

The Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences experience, according to three recent graduates

Bachelor of Applied Arts and Sciences students shine in the first annual Senior Colloquium

How to become a data-oriented thinker and problem-solver in the Certificate in Data Analytics

Literature, Culture, and Tradition: an online degree concentration for students of humanity

Informative, introspective, and inspiring: 12 interesting Ivy League courses you can take online this fall

Achieve your unique goals with flexible degree requirements and a custom Penn experience

What are certificates—and why do working professionals increasingly find them worthwhile?

Online learning isn’t a replacement for the campus classroom. For some students, it’s better.

Skill, style, and substance: How creative writing workshops fuel personal and professional growth

With ‘The Sacramento of Desire,’ creative writing professor Julia Bloch completes a personal trilogy